The Plains Indians had a very distinct artistic style based on the raw materials they had available. The focus of this paper is on the rendezvous, or fur trade, period. In addition, the concentration is on the art of the Plains Indian woman. Most of the primary written documentation is filtered through the eyes of white men of the period which of course was different from that of the present time. In addition, the archaeological evidence is also primarily filtered through the eyes of white male archeologists (Kehoe). They saw what they expected to see: women very much in the background doing the drudge work while men concentrated on lounging around being served by the women. This was an oversimplified version of the reality (Albers and Medicine). Even though primary written documentation was from white males we do have “grandmother stories” from many irrefutable sources such as Waterlily (Deloria), Daughters of the earth (Niethammer), Grandmother’s Grandchild (Snell), Women of the Earth Lodges (Peters), etc.

The materials used by the Plains Indian women were those that were available: primarily buffalo, as well as elk, moose, antelope, and big horn sheep hides, rawhide, furs, and sinew. Additionally, porcupine quills and dyes to color them were used to produce a shiny, colorful and decorative medium to embellish clothing, accouterments, and sacred objects, as well as everyday items (Sundstrom). As cloth, beads and thread became available, these new materials were used more widely which, as sewing beads on cloth was faster than quillwork, hastened the demise of traditional quillwork. Quillwork also had sacred meaning that beadwork did not have so that beads were more suitable for trade items that were not going to be used by family or The People (Sundstrom).

The most impressive component of the beautiful art pieces made by women in that era is not so much the designs, though exquisite, or color choice, or any single element, but the ability of the women to create such amazing works while doing all the other things that had to be done in order to survive. Hauling water and wood, gathering plants and berries, to eat or process for drying, and cooking a minimum of two meals a day while being ready to graciously serve any number of guests at any moment. These artists spent their time drying meat, pounding it into powder for pemmican, rendering fat for same, all under primitive conditions while tending children and taking care of hunter/warrior husband. Native American women were ready, able, and willing, to pack up and move their tipi and all their worldly goods whenever necessary. In addition, they tanned all the hides, made them into bed coverings, clothing; dresses, leggings, shirts as well as moccasins (minimum of six pairs a year per person in family). Also any tipi furnishings such as backrests, storage containers made from rawhide, eating utensils; bowls, spoons, ladles. Native American women did all of this and more and decorated everything to make life gracious and beautiful as well as sacred. Her work, artistry and hospitality could affect her husband’s social position as well as her own and her children’s (Deloria).

Cradle boards were made by the mother, aunts or grandmothers depending on the tribe and circumstances.

The materials used by the Plains Indian women were those that were available: primarily buffalo, as well as elk, moose, antelope, and big horn sheep hides, rawhide, furs, and sinew. Additionally, porcupine quills and dyes to color them were used to produce a shiny, colorful and decorative medium to embellish clothing, accouterments, and sacred objects, as well as everyday items (Sundstrom). As cloth, beads and thread became available, these new materials were used more widely which, as sewing beads on cloth was faster than quillwork, hastened the demise of traditional quillwork. Quillwork also had sacred meaning that beadwork did not have so that beads were more suitable for trade items that were not going to be used by family or The People (Sundstrom).

The most impressive component of the beautiful art pieces made by women in that era is not so much the designs, though exquisite, or color choice, or any single element, but the ability of the women to create such amazing works while doing all the other things that had to be done in order to survive. Hauling water and wood, gathering plants and berries, to eat or process for drying, and cooking a minimum of two meals a day while being ready to graciously serve any number of guests at any moment. These artists spent their time drying meat, pounding it into powder for pemmican, rendering fat for same, all under primitive conditions while tending children and taking care of hunter/warrior husband. Native American women were ready, able, and willing, to pack up and move their tipi and all their worldly goods whenever necessary. In addition, they tanned all the hides, made them into bed coverings, clothing; dresses, leggings, shirts as well as moccasins (minimum of six pairs a year per person in family). Also any tipi furnishings such as backrests, storage containers made from rawhide, eating utensils; bowls, spoons, ladles. Native American women did all of this and more and decorated everything to make life gracious and beautiful as well as sacred. Her work, artistry and hospitality could affect her husband’s social position as well as her own and her children’s (Deloria).

Cradle boards were made by the mother, aunts or grandmothers depending on the tribe and circumstances.

Buffalo robes were first tanned then painted, quilled or beaded. Buffalo skin was also processed into rawhide for parfleche, the storage container of the plains. The buffalo was everything: food, shelter, warmth. When the white man wanted to destroy the Plains Indian way of life and force them on the reservation, they slaughtered the buffalo and left them to rot.

Personal adornment was comprised of body painting as well as clothing and accouterments. Plains Indians used bear and buffalo grease to protect the skin from wind and sun and it had pigment, primarily red ochre, mixed into it and applied to the skin (Conn). There were many different markings and symbols for various purposes outside the scope of this paper. With that said, it was an extensively used form of decoration.

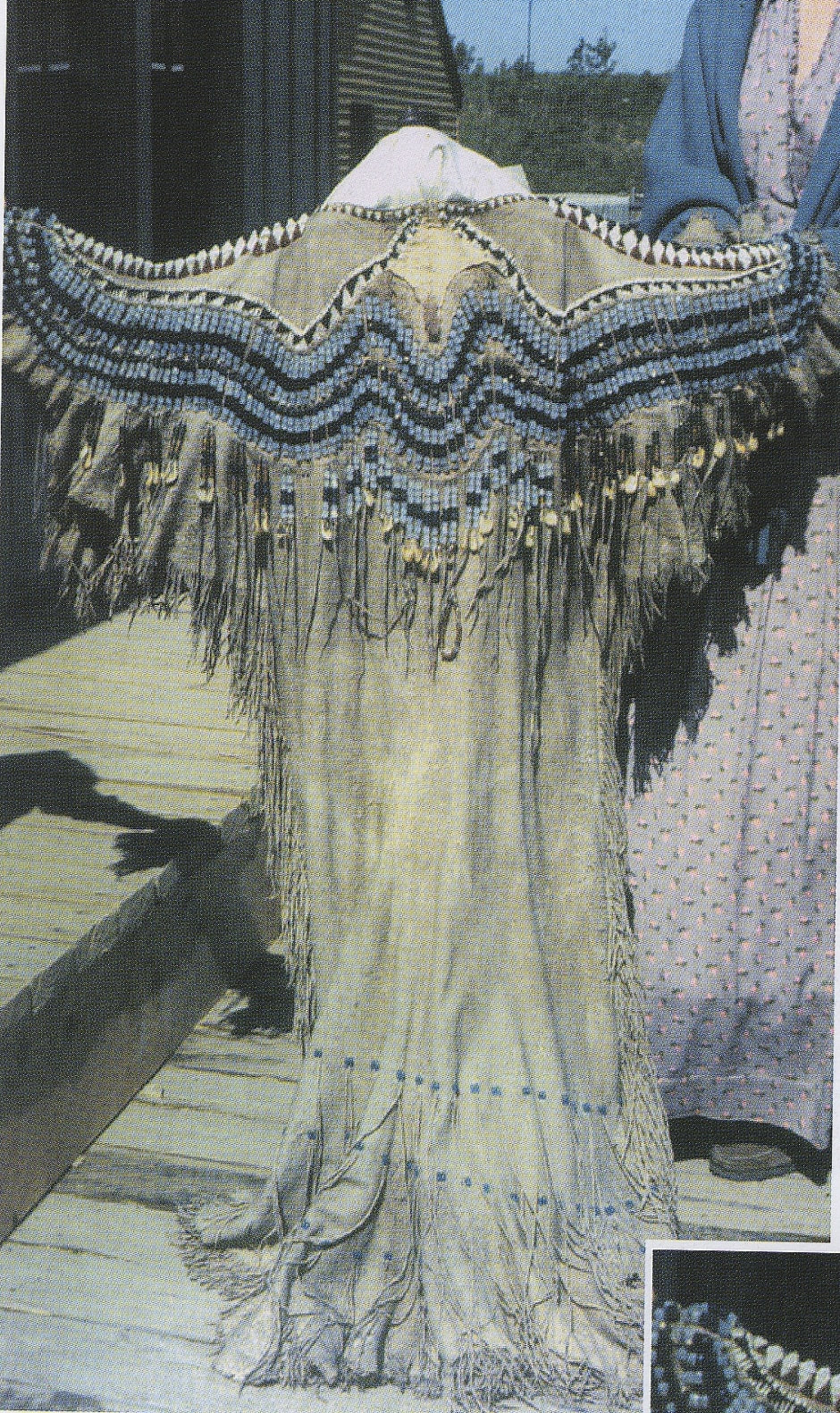

Native women of the plains made dresses recognized for their beauty, each dress telling its own story as to the artistry of the maker, the status and wealth of the family and social worth of the creator (Identity by Design) (Conn). Decorations on dresses were comprised of quillwork, glass beads, paint or pigment, embellished with thimbles, tin cones, elk teeth, cowrie shells, or trade cloth. Dresses of the Plains were generally of four types: strap dress, side fold, two hide and three hide style (Taylor). The two or three hide deer tail dress was perhaps a result of the horse culture, the two hide style was much fuller allowing the women to ride astride a horse (Taylor). The Plains women kept the hides intact and used the shapes as they came off of the animals, legs and neck hide included. The top of the hide folded down and the tail formed decoration as part of the yoke on the chest. The beading or quillwork was done in an undulating pattern to accent the tail. Even if the tail wasn’t actually there, the beading formed that shape on the front and back. In general the beading was symmetrical on the front and back (Jennys). There were differences of decoration and bottom hem shape from tribe to tribe. However, through trade and gifting styles were copied and fashions changed over time (Taylor). Most of the Plains women had a dress-up or ceremonial outfit and then an everyday or work dress. A woman would not be scraping hides in her best dress! (Langstein).

Personal adornment was comprised of body painting as well as clothing and accouterments. Plains Indians used bear and buffalo grease to protect the skin from wind and sun and it had pigment, primarily red ochre, mixed into it and applied to the skin (Conn). There were many different markings and symbols for various purposes outside the scope of this paper. With that said, it was an extensively used form of decoration.

Native women of the plains made dresses recognized for their beauty, each dress telling its own story as to the artistry of the maker, the status and wealth of the family and social worth of the creator (Identity by Design) (Conn). Decorations on dresses were comprised of quillwork, glass beads, paint or pigment, embellished with thimbles, tin cones, elk teeth, cowrie shells, or trade cloth. Dresses of the Plains were generally of four types: strap dress, side fold, two hide and three hide style (Taylor). The two or three hide deer tail dress was perhaps a result of the horse culture, the two hide style was much fuller allowing the women to ride astride a horse (Taylor). The Plains women kept the hides intact and used the shapes as they came off of the animals, legs and neck hide included. The top of the hide folded down and the tail formed decoration as part of the yoke on the chest. The beading or quillwork was done in an undulating pattern to accent the tail. Even if the tail wasn’t actually there, the beading formed that shape on the front and back. In general the beading was symmetrical on the front and back (Jennys). There were differences of decoration and bottom hem shape from tribe to tribe. However, through trade and gifting styles were copied and fashions changed over time (Taylor). Most of the Plains women had a dress-up or ceremonial outfit and then an everyday or work dress. A woman would not be scraping hides in her best dress! (Langstein).

Belts were often made of rawhide with painted and/or incised designs, also quilled or beaded. Sometimes the belt indicated social status or an honor earned: “For my industry in dressing skins, my clan aunt Sage, gave me a woman’s belt. It was as broad as my three fingers, and covered with blue beads…only a very industrious girl was given such a belt. She could not buy or make one. To wear a woman’s belt was an honor. I was as proud of mine as a war leader of his first scalp” (Wilson) p117-118.

Awl cases were often beautifully quilled or beaded. The awl was an extremely important tool both from a practical as well as a symbolic perspective, “With it a woman made the clothing and shelter that protected her family from the dangers of the outside world. She used it to create items from cradles to moccasins that would surround her loved ones with protective symbols and remind them of their values and identity” (Sundstrom) p 100. Awls were made of bone until contact with European trade goods, and then metal awls, needles, and hide processing tools were used. Most lists of things traded for hides and pelts refer to awls and needles showing that these articles were highly desired (Sundstrom).

Plains Indian women were skilled, creative and inspired at making head pieces and hair decorations, everything from braid wraps of otter fur, wool and leather to upright feather headdresses to hair bows with ribbon streamers and silver buttons. Rawhide visors were also painted.

Awl cases were often beautifully quilled or beaded. The awl was an extremely important tool both from a practical as well as a symbolic perspective, “With it a woman made the clothing and shelter that protected her family from the dangers of the outside world. She used it to create items from cradles to moccasins that would surround her loved ones with protective symbols and remind them of their values and identity” (Sundstrom) p 100. Awls were made of bone until contact with European trade goods, and then metal awls, needles, and hide processing tools were used. Most lists of things traded for hides and pelts refer to awls and needles showing that these articles were highly desired (Sundstrom).

Plains Indian women were skilled, creative and inspired at making head pieces and hair decorations, everything from braid wraps of otter fur, wool and leather to upright feather headdresses to hair bows with ribbon streamers and silver buttons. Rawhide visors were also painted.

Moccasins were very necessary on the plains and they wore out frequently. Moccasins could be re-soled but new ones were often needed. Women would need to make moccasins on an almost constant basis and a competent woman could probably whip up a pair in an afternoon. The decorative part of the moccasins would probably take a little longer, depending on the complexity of the design and the decorative elements used, for instance quillwork or beading. Fully quilled or beaded moccasins, including the soles, were made for ceremonies or weddings where the value of a person wearing them was very high showing that they need not walk on the ground.

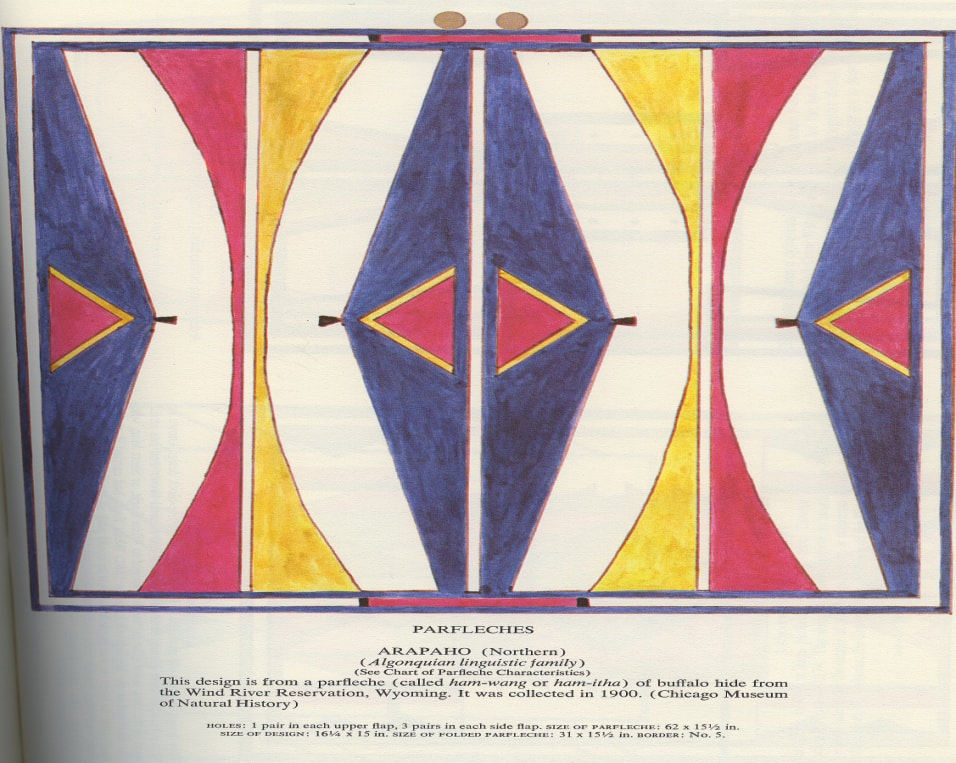

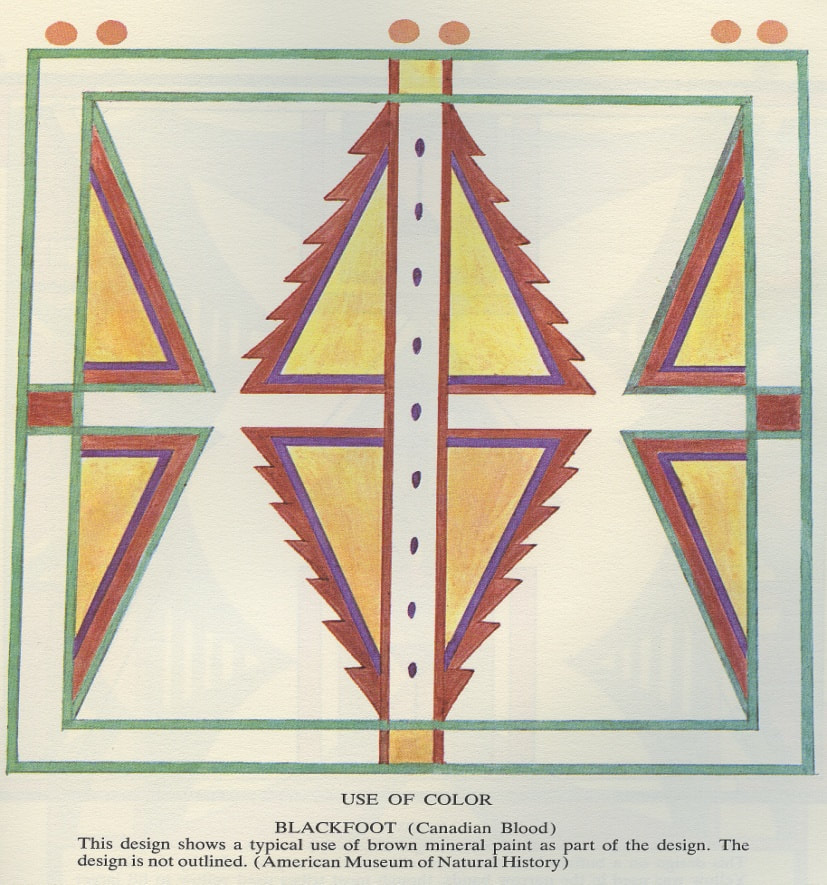

Containers to store everything were made of rawhide, two large cases could be made from one buffalo rawhide, early buffalo parfleche were incised with the design, as it dried, it expanded, leaving a two toned design. The buffalo hide was staked out and scraped of all fat and flesh. While still wet, it was painted with a personal design or a design indicating what was stored inside (Morrow). A woman had her own design or a family design in order to differentiate the belongings when they were cached (Deloria). Parfleche, from the French “parer fleche to turn away arrows” (Berlo and Phillips) were used to store dried meat, dried berries, clothing, tent stakes or stakes for staking out hides, extra clothing, paint cases, sewing implements and supplies, anything that needed to be kept waterproof including round headdress cases for the men. Additionally rawhide was used for burden straps, cradles, lodge doors, drums, sun visors, horse trappings, knife sheaths, masks, mortar and pestles, shields, and toys (Morrow).

Containers to store everything were made of rawhide, two large cases could be made from one buffalo rawhide, early buffalo parfleche were incised with the design, as it dried, it expanded, leaving a two toned design. The buffalo hide was staked out and scraped of all fat and flesh. While still wet, it was painted with a personal design or a design indicating what was stored inside (Morrow). A woman had her own design or a family design in order to differentiate the belongings when they were cached (Deloria). Parfleche, from the French “parer fleche to turn away arrows” (Berlo and Phillips) were used to store dried meat, dried berries, clothing, tent stakes or stakes for staking out hides, extra clothing, paint cases, sewing implements and supplies, anything that needed to be kept waterproof including round headdress cases for the men. Additionally rawhide was used for burden straps, cradles, lodge doors, drums, sun visors, horse trappings, knife sheaths, masks, mortar and pestles, shields, and toys (Morrow).

Native American women of the 1825-1840 fur trade time period were amazing artists and homemakers in spite of, or perhaps because of, their nomadic life style. The more I learn the more I am in awe of the breadth and depth of their knowledge and skills.

Bibliography

Albers, Patricia and Beatrice Medicine. The Hidden Half. New York: University Press of America, 1983.

Berlo, Janet C and Ruth B. Phillips. Native North American Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Conn, Richard. Robes of White Shell and Sunrise, Personal Decorative Arts of the Native American. Denver: Denver Art Museum, 1974.

Deloria, Ella Cara. Waterlily. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1988.

"Identity by Design." National museum of the American Indian. 27 January 2012 <http://americanindian.si.edu/exhibitions/identity_by_design/IdentityByDesign.html>.

Jennys, Susan. 19th Century Plains Indian Dresses. Pottsboro: Crazy Crow Trading Post, 2004.

Kehoe, Alice Beck. "Women Appear in the Plains." Archaelolgies: Journal of the World Archaeological Congress (2011): 154-169.

Langstein, Christina. Women of the Fur Trade Journal Mary J. Hipol. 3 September 2009.

Morrow, Mable. Indian rawhide: an American folk art. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1974.

Niethammer, Carolyn. Daughters of the earth. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1977.

Peters, Virginia Bergman. Women of the earth lodges. North Haven: Archon Books, 1995.

Snell, Alma Hogan. Grandmother's Grandchild. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2000.

Sundstrom, Linea. "Steel Awls for Stone Age Plainswomen: Rock Art, Religion, and the Hide Trade on the Northern Plains." Plains Anthropologist (2002): 99-119.

Taylor, Colin F. Yupika, The Plains Indian Woman's Dress. Germany: Verlag fur Amerikanistik, 1997.

Wilson, Gilbert L. Waheenee: An Indian Girl's Story Told by Herself to Gilbert L. Wilson. Linclon: University of Nebraska Press, 1981.

Albers, Patricia and Beatrice Medicine. The Hidden Half. New York: University Press of America, 1983.

Berlo, Janet C and Ruth B. Phillips. Native North American Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Conn, Richard. Robes of White Shell and Sunrise, Personal Decorative Arts of the Native American. Denver: Denver Art Museum, 1974.

Deloria, Ella Cara. Waterlily. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1988.

"Identity by Design." National museum of the American Indian. 27 January 2012 <http://americanindian.si.edu/exhibitions/identity_by_design/IdentityByDesign.html>.

Jennys, Susan. 19th Century Plains Indian Dresses. Pottsboro: Crazy Crow Trading Post, 2004.

Kehoe, Alice Beck. "Women Appear in the Plains." Archaelolgies: Journal of the World Archaeological Congress (2011): 154-169.

Langstein, Christina. Women of the Fur Trade Journal Mary J. Hipol. 3 September 2009.

Morrow, Mable. Indian rawhide: an American folk art. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1974.

Niethammer, Carolyn. Daughters of the earth. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1977.

Peters, Virginia Bergman. Women of the earth lodges. North Haven: Archon Books, 1995.

Snell, Alma Hogan. Grandmother's Grandchild. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2000.

Sundstrom, Linea. "Steel Awls for Stone Age Plainswomen: Rock Art, Religion, and the Hide Trade on the Northern Plains." Plains Anthropologist (2002): 99-119.

Taylor, Colin F. Yupika, The Plains Indian Woman's Dress. Germany: Verlag fur Amerikanistik, 1997.

Wilson, Gilbert L. Waheenee: An Indian Girl's Story Told by Herself to Gilbert L. Wilson. Linclon: University of Nebraska Press, 1981.